David Pearson on Phillumeny

~ While Alistair is away cycling the length of Great Britain, we've invited twenty disgustingly talented people to each write a post for our blog. Today's post is from one of our studio partners, the irritatingly brilliant book designer David Pearson. ~

Around five years ago Alistair invited me along to an ephemera fair in Bloomsbury. Like a lot of designers I can be a bit of a magpie and have always been susceptible to collecting, arranging, colour- and number-coding (see, for example, all of my work) so I was in trouble when I stumbled across a container full of matchbox labels. Membership to the British Matchbox Label and Bookmatch Society; 50,000 matchbox labels; and a half-written book later, I’m slowly getting to grips with my latest print-based addiction.

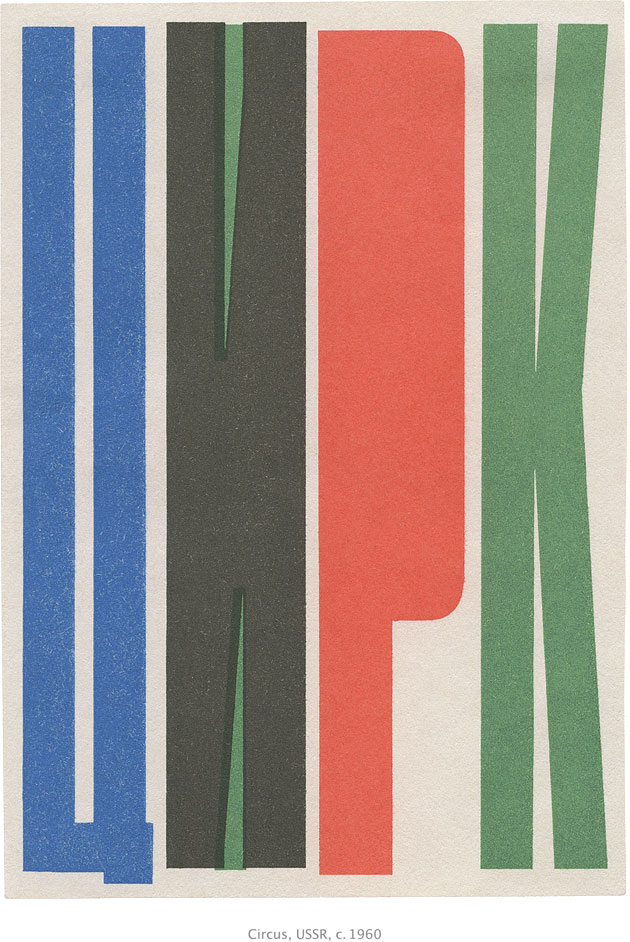

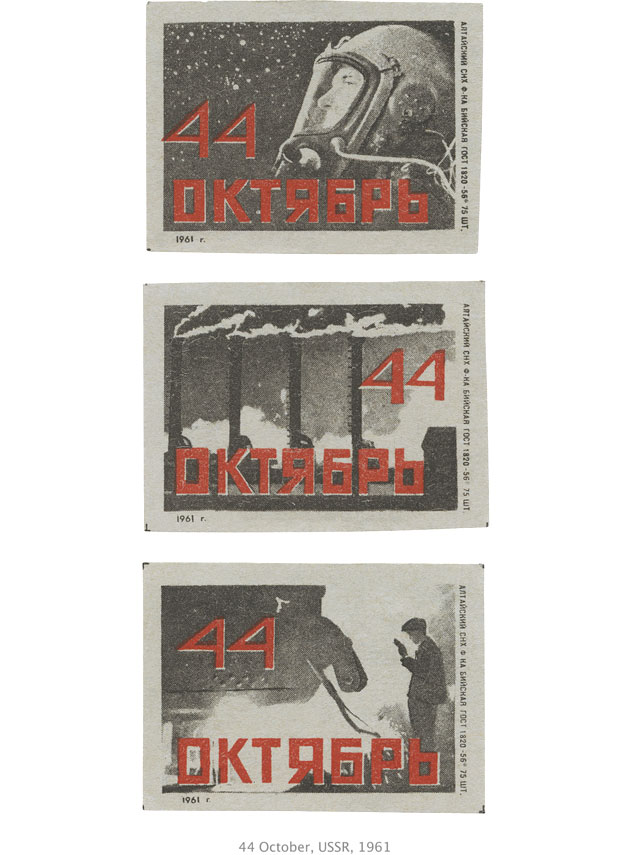

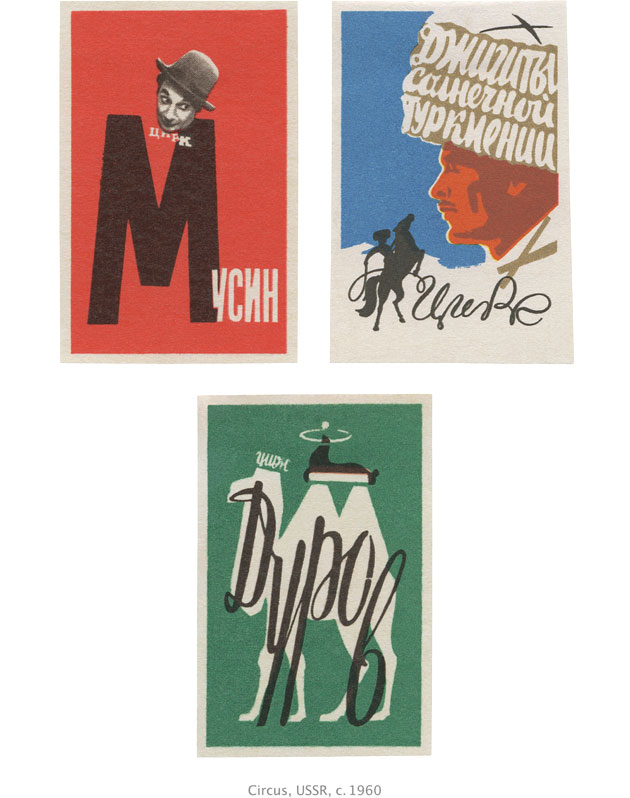

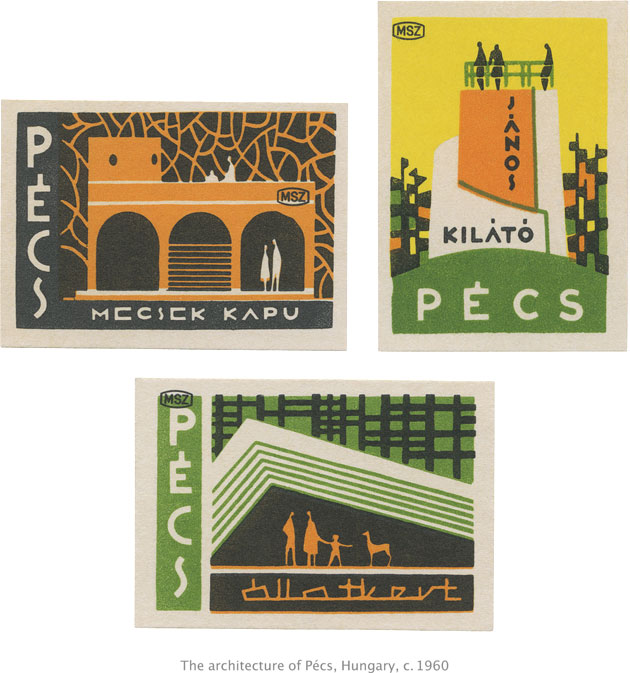

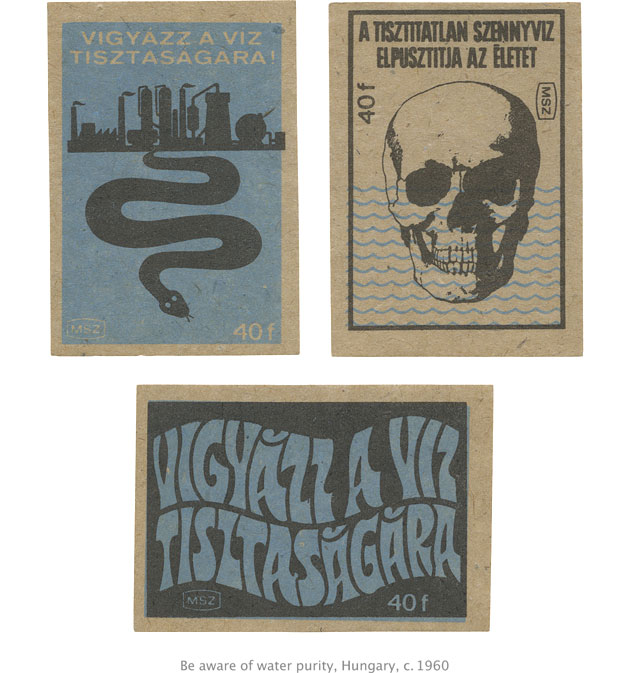

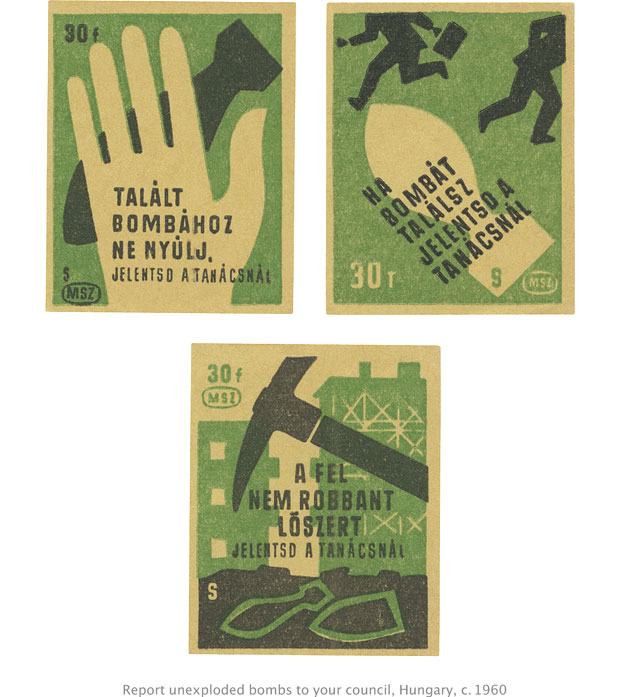

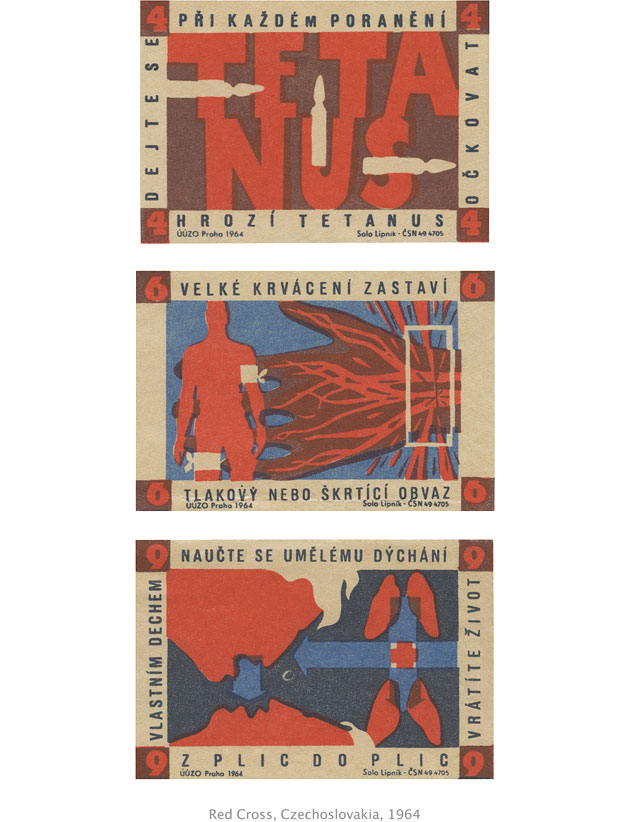

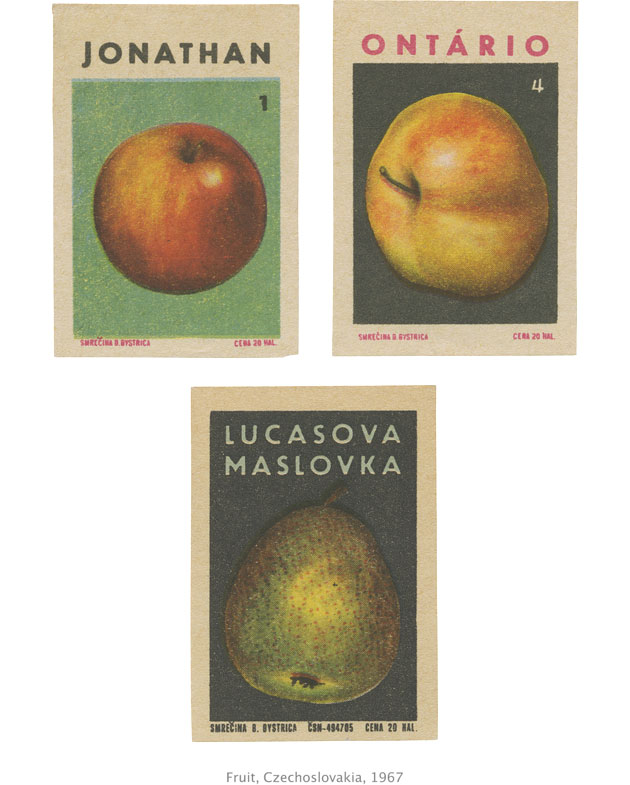

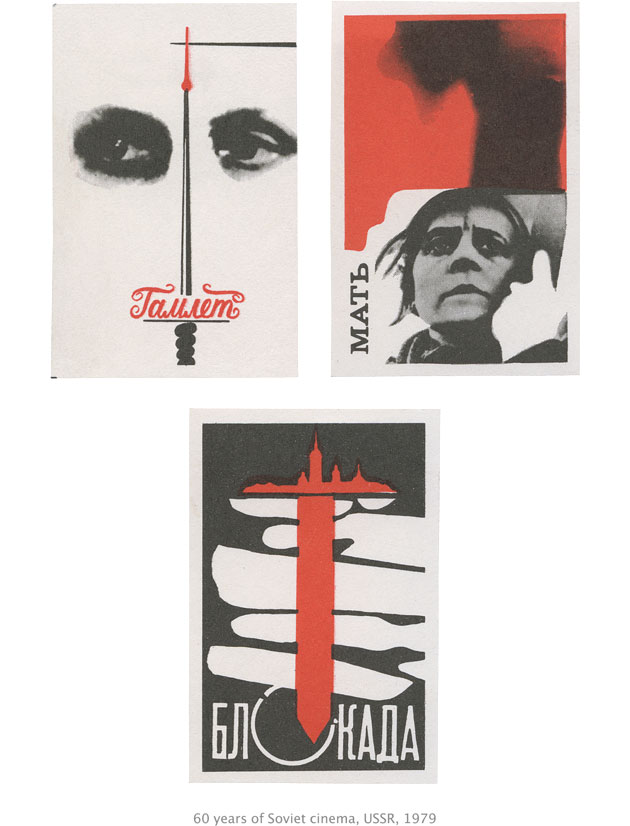

In the former Soviet Bloc countries of Eastern Europe, the matchbox as a means of delivering propaganda had no equal. Readily available, cheap and collectible, matchboxes and their printed labels presented idealistic images promoting communism as the moderniser of society.

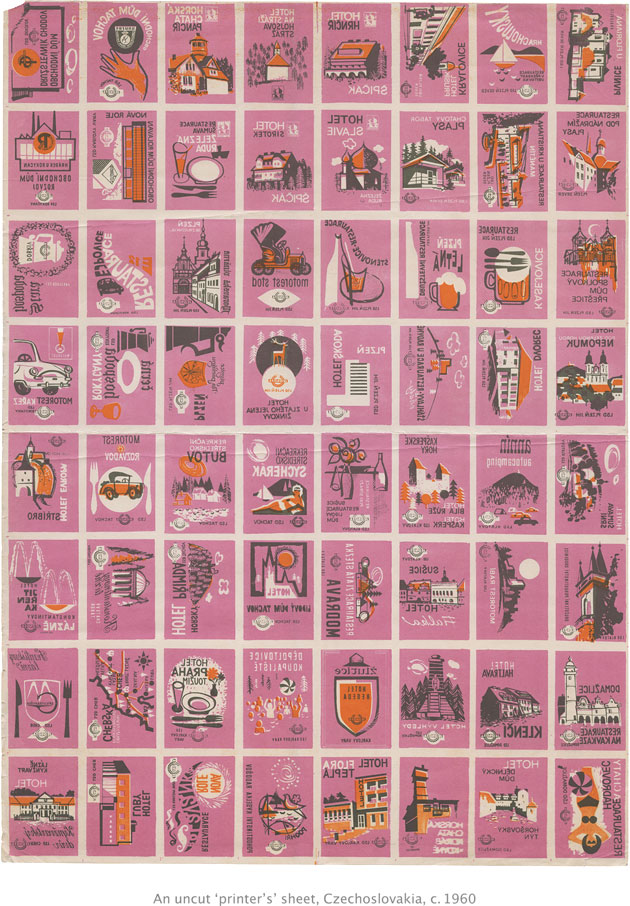

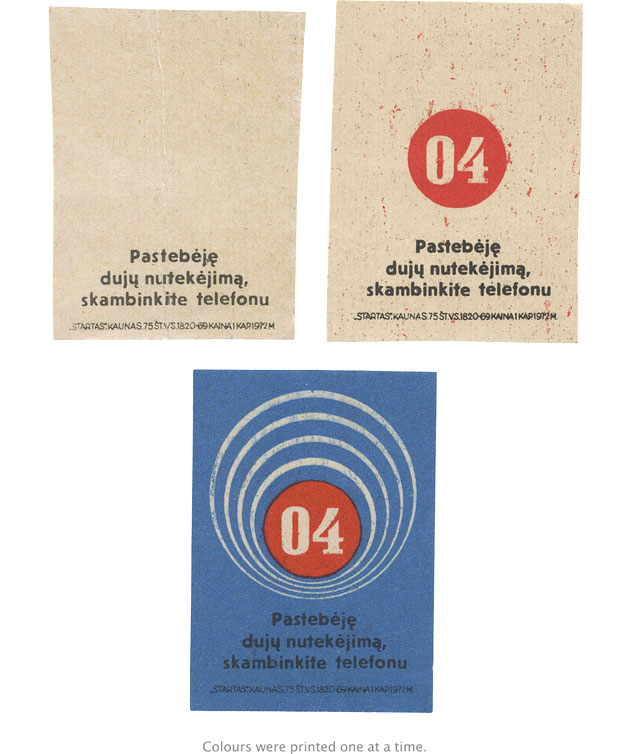

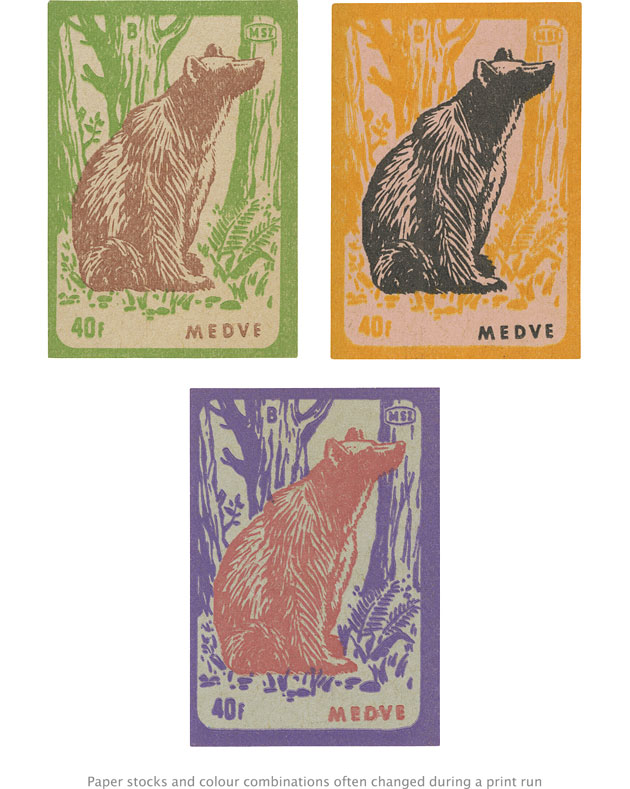

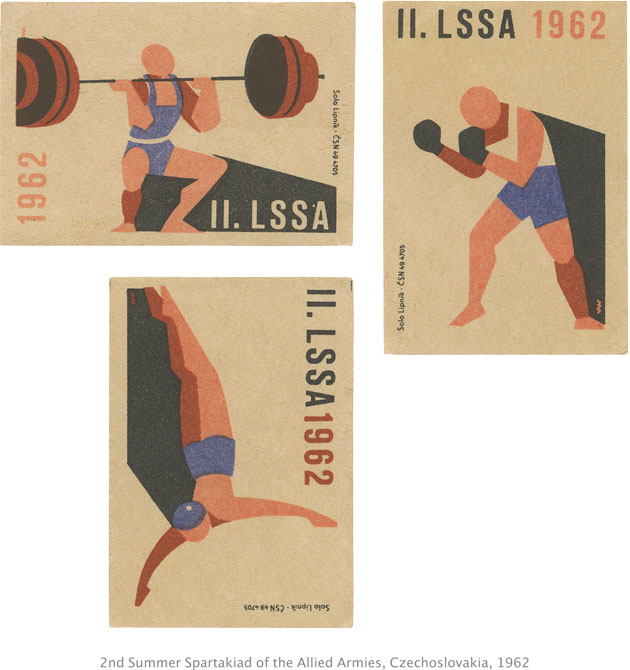

The images displayed here are the output of four Eastern Bloc countries (Russia, Hungary, Lithuania and Czechoslovakia), from 1956–79. During this period, post-Stalinist Russia and its satellite states were struggling to free themselves from authoritarian state policies, but relative liberalisation provided some optimism after years of material deprivation. For the first time, Western advertising models were adopted and ‘cultured’ consumption encouraged, with the emphasis on individual and family happiness. The result was a new vision of civilisation and the matchbox label was key to the widespread circulation of this message.

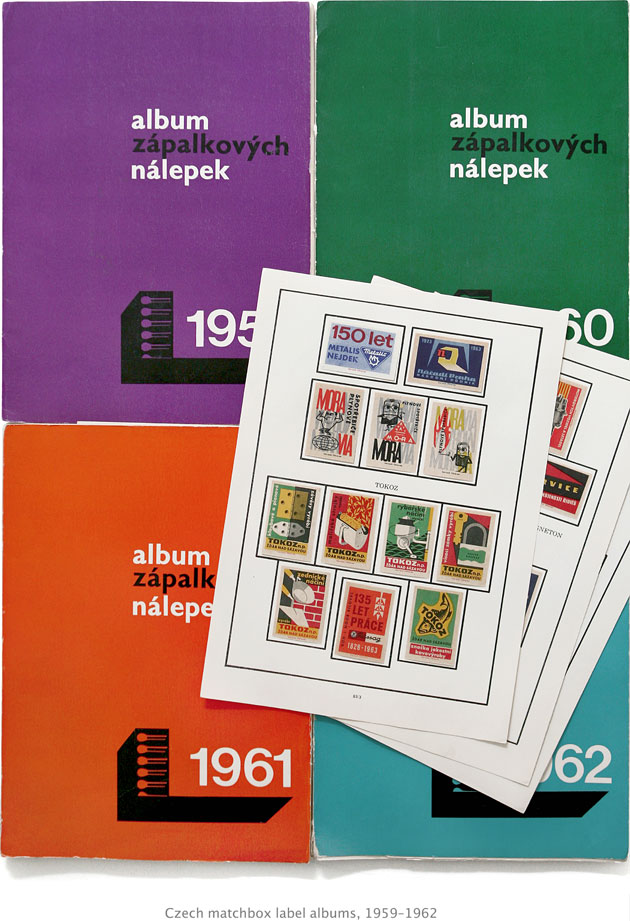

Collectors’ associations were encouraged by the authorities in many of the Eastern Bloc countries and this resulted in the printing and distribution of huge quantities of labels – often in their uncut form – providing collectors with access to complete, themed series. In the case of Czechoslovakia, dedicated albums were produced to house collections, and Russian labels were often packaged in gift sets for the export market. These otherwise ephemeral objects would therefore long outlive the boxes of matches they were designed for.

Reproduction can be crude – with overprinted colours regularly appearing out of register – but such quirks can provide the collector with a uniquely interesting acquisition and enliven compositions in unexpected ways.

It’s no coincidence that a book designer should be drawn to matchbox labels. Their shape is intrinsically book-like, their method of communication instantaneous and spare, and they provide a dizzying range of illustrative styles. Their uncluttered compositions ensure communication across language barriers, and designs appear cohesive as a result of type and image being rendered by the same hand. But perhaps most alluring of all is their uncompromised clarity of purpose, an attribute that most modern designers can only dream about.

Generally speaking, matchbox labels aren’t valuable. The examples shown here were amassed for pence rather than pounds and owing to their vast numbers, generally considered a nuisance by collectors more interested in scarcity. My own labels are stored in stamp collecting folders that far outweigh their contents in terms of cost.

Perhaps this hints at the reason why matchbox labels are rarely of interest to art critics and almost never to cultural historians; but of all the visual images displayed by a culture, the matchbox must be ranked amongst the most democratic and accessible, and it therefore provides us with a fascinating study of a fast-changing social landscape.

- A NOTE ABOUT THE IMAGES -

Over the past few years, matchbox labels have become increasingly visible thanks to wonderful online collections such as Jane McDevitt’s. As much as possible, I have tried to avoid duplicating Jane’s images here, so do take a look at her collection if you’re hungry for more.

I have chosen to show just three labels from each themed series but in general, Russian export sets run to sixteen small labels (54mm x 35mm), one medium-sized label (107mm x 70mm) and one large label (228mm x 113mm). Czech groupings range from anywhere between two and 64 small labels whilst Hungarian and Lithuanian sets are most commonly found in groups of nine small labels.

~ Alistair is raising money for Cancer Research UK during his ride - please wander over to his Just Giving page and donate a little cash. ~